Carl Alfred Lanning Binger, 1889-1976

A few weeks ago, in a lockdown phone call, my ninety-year-old mother Bici reminded me that her father Carl Binger had served as an army doctor in France during World War I, at the peak of the 1918 influenza epidemic. Across the Western Front the flu was killing more soldiers than the war itself. My grandfather found himself on the frontlines of the medical response and of research on how to contain the contagion. While he didn’t discover much about the pathogen itself, through careful observation and common sense he and his colleagues helped slow the spread of the virus – screening and isolating sick soldiers, reducing the density of sleeping quarters, and using tents for recuperation at field camps rather than transporting sick soldiers to over-crowded wards in base hospitals.

My curiosity was peaked. What could be more interesting than finding out about my grandfather’s role in quarantine efforts during the flu pandemic a century ago? So I poured some of my lockdown angst into online research. Bici recalled that he had been stationed at Boulogne, but searches of “American Base Hospital No 5” there produced no results for a Dr Binger. However, I did learn that the Boulogne base hospital was organized by Harvard University. Carl Binger had graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1914 and was then at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston – Bici thinks he was the first Jewish doctor to become a resident there. Hot on the trail, I discovered that MGH had set up “American Base Hospital No 6”, in Bordeaux, and found a detailed 1924 account by some of the doctors, nurses and officers who had been stationed there. And Bingo! …there were no less than 33 references to “Lieutenant Binger”.

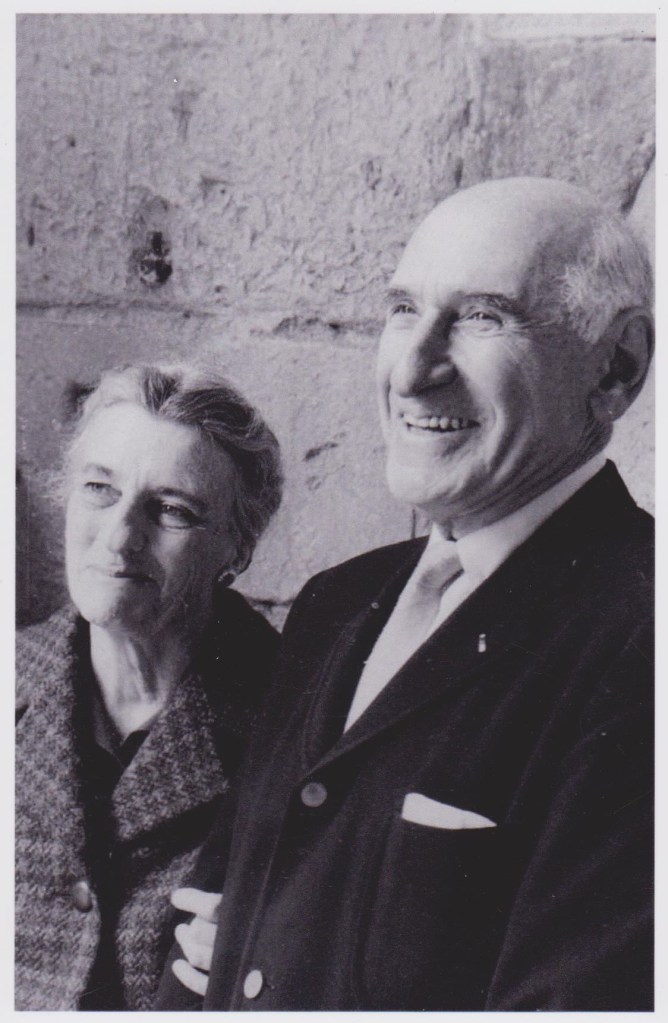

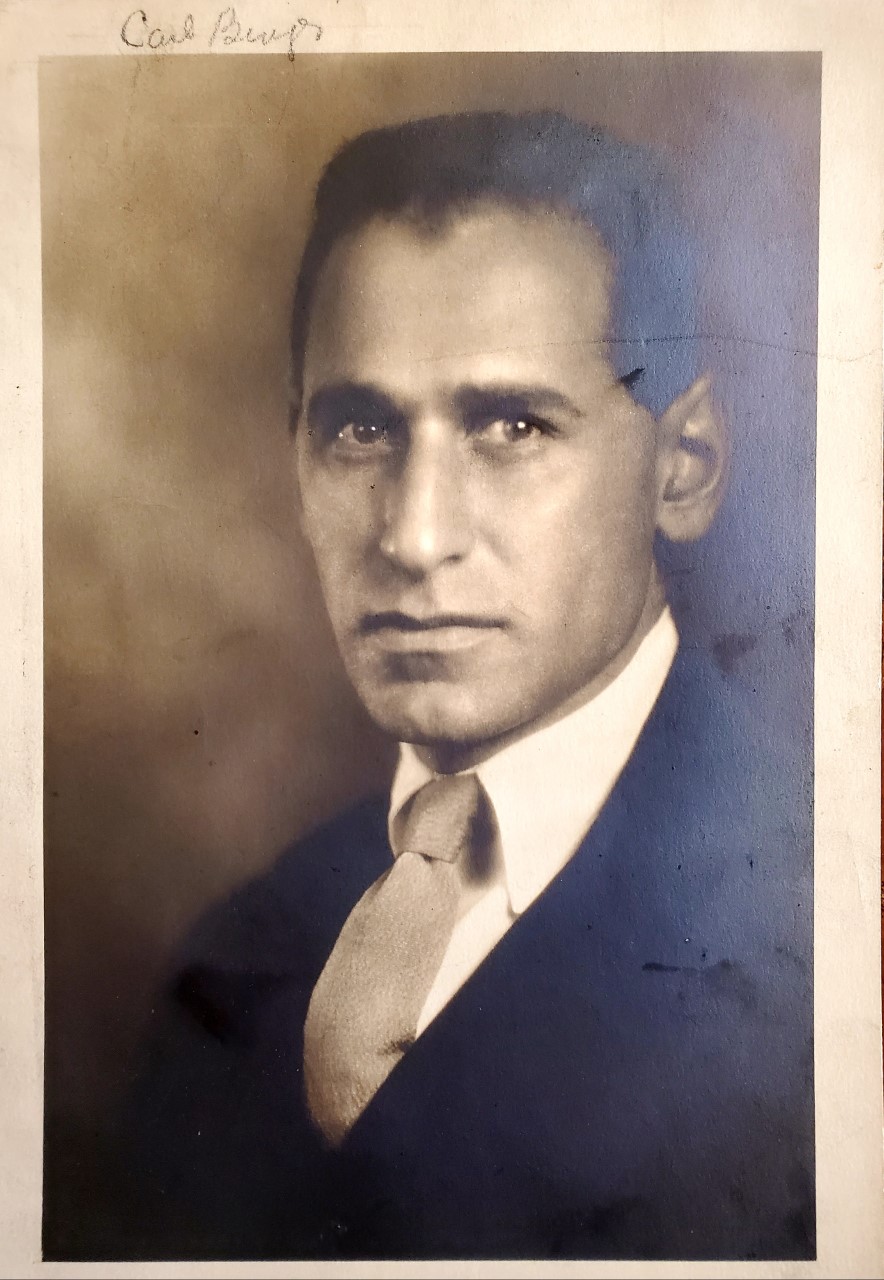

I was 17 when my grandfather died in 1976, at the age of 87, and have fond memories of his kind and gentle if somewhat formal nature, at least with young children. We grandchildren (nine of us) knew him as “Dante”, a humorous affection derived from my mother being “Beatrice” and from a grandchild trying to say “Grandpa”, which he immediately seized upon and turned into Dante. He taught me how to shake hands firmly, looking the other person straight in the eye, by gripping my hand until it hurt. Tried as I did, I never succeeded in out-squeezing him, even in his old age. By then he was a well-known psychiatrist and popular author, a pioneer of psychosomatic medicine, had studied with Carl Jung, and had famously testified against Whittaker Chambers in the Alger Hiss trial – the first time psychiatric evidence was admitted in a US court.

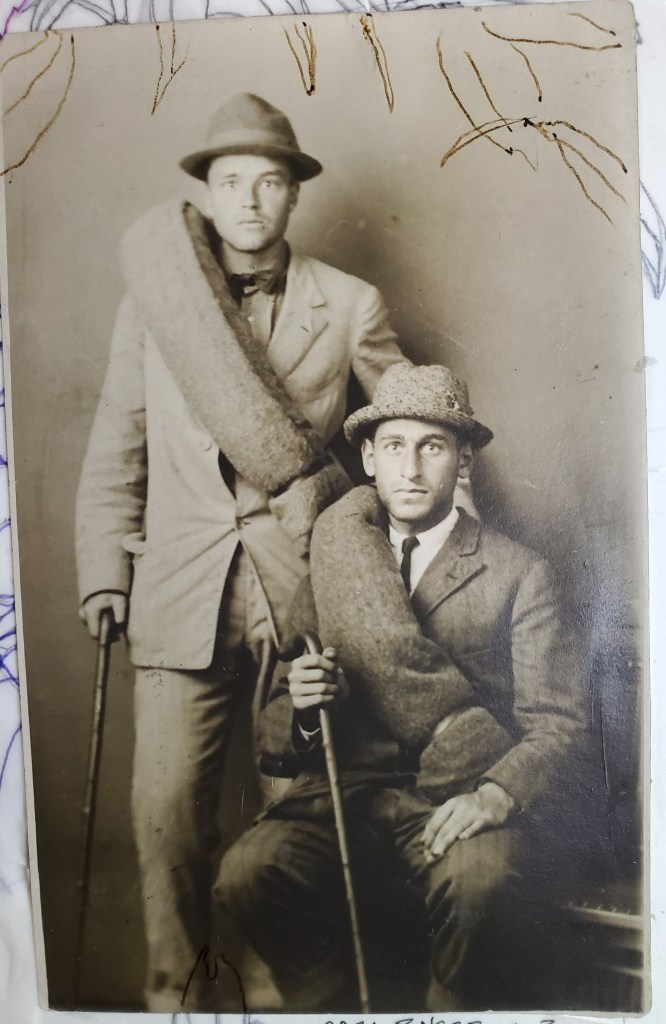

Carl Alfred Lanning Binger (“CALB” as he is sometimes referred to by the older generation) was born at a seaside resort in New Jersey, owned by the journalist Alfred Lansing. His father Gustav had emigrated in 1867 from Arnhem, Holland, to take over the family’s leather business. Carl graduated from Harvard College in 1906 and went on to the medical school. He interned at Bellevue City Hospital in New York before joining MGH. Though eventually, in his mid-30s, he became a psychiatrist, he was first very much a physician and research scientist, specialising in infectious disease and later pulmonary medicine – possibly in the wake of his encounter with so much deadly pneumonia during the great war. He later helped develop the first oxygen therapies and breathing devices – the iron lung and the portable oxygen tent – and one of his first psychosomatic studies was on the “psycho-biology” of breathing in asthma patients.

American Base Hospital No. 6

Even before the US entered WWI, in 1916, US hospitals and medical schools had begun creating “reserve hospitals” in partnership with the American Red Cross. These were repositories of hospital supplies and rosters of doctors, nurses and other personnel ready and willing to serve. When the call came in May of 1917, MGH mobilized hundreds of nurses, doctors and other skilled personnel to train at Fort Strong, on an island in Boston Harbor. On July 8th they marched quietly to South Station, boarded a train to New York, and sailed on July 11th from Ellis Island on the Auriana. Their vessel was escorted by the Navy, which at one point fired torpedoes to ward off a German submarine. On a later voyage, the Auriana was attacked and sank.

Arriving in Liverpool, the hospital crew went by train to Southampton and sailed the next day to Le Havre. A nurse described the comradery and organization on the voyage, the continual training, how strange it was to travel across England without seeing a single able-bodied man. Nurse Sara Parsons recalled that “The sight of so many old women and children working in the fields and gardens, who waved and cheered our train as we passed, made lumps rise in our throats and the landscape a blur” (Parsons, 1924 account, p.52). The MGH crew still didn’t know where they were destined, but eventually they were put on a special train to Bordeaux, where Base Hospital No. 6 was established.

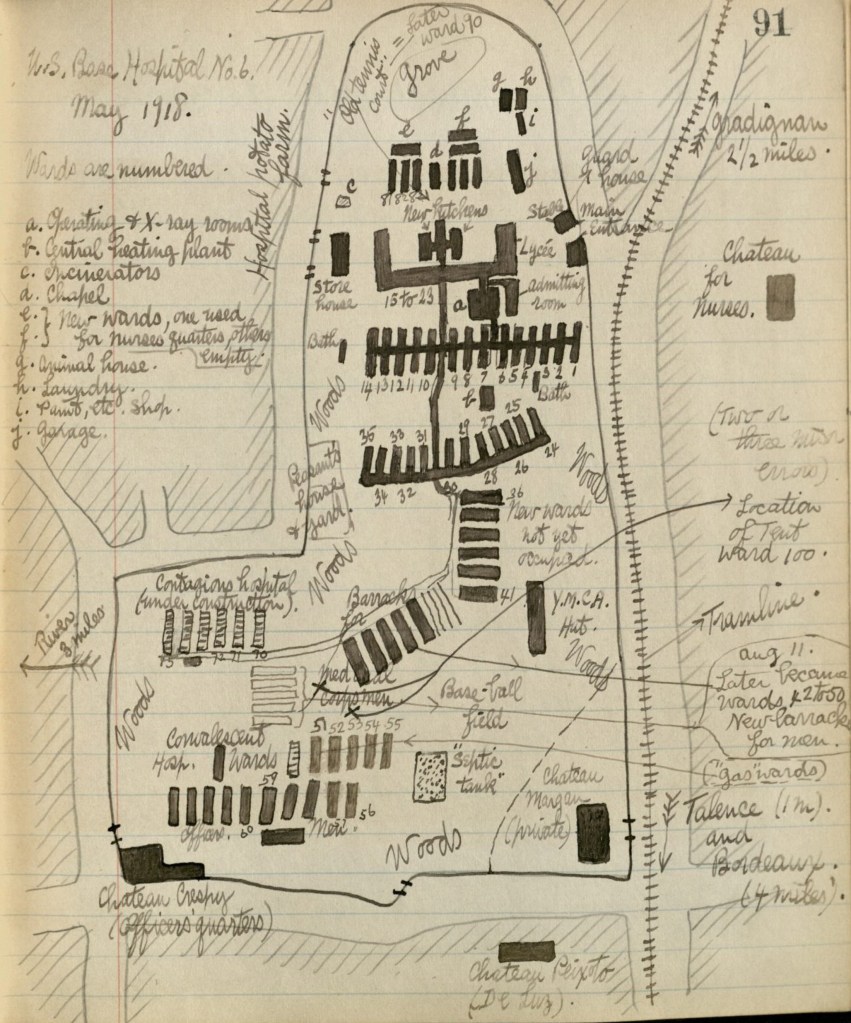

Taking over a small temporary French military hospital located in the “Petit Lycée de Bordeaux”, a boys’ school in Talence, just south of Bordeaux, the MGH team set to work creating into a 1000-bed hospital. American carpenters, plumbers, and electricians worked alongside French builders to construct additional wards, kitchens, storerooms, stables, gardens and barracks, and to install water lines, sewage, electrical wiring and heating. Nearby “chateaux” (mansions rather than castles, as far as I can tell from pictures) were turned into residences for nurses and officers, and the grounds of these estates were used for row upon row of barracks and wards. A hand drawn map from a medical history archive in Boston shows how vast the installation became. The French were particular about saving old trees on these estates, which the Americans wanted to fell to make way for a modern linear construction. To the Army engineers’ dismay the new wards had to snake around the trees, connected by covered walkways.

Today there is not a single hint of the hospital’s existence on Google Maps, but by inverting the image to North-South, using satellite view to find the “chateaux” and finally locating the elongated H-shaped school building (now the Lycée Victor Louis, “temporarily closed” no doubt due to the coronavirus lockdown), I was able to trace the unmistakable footprint of American Base Hospital No 6. Continuing my virtual archaeology by cruising around the area on streeetview, I found views of the chateaux that remain, including what could be the now-dilapidated Chateau Crespy which had served as the officers’ quarters, and is where my grandfather probably lived. My mother remembers that he gave his quarters to his brother Walter when he visited Carl, infected with the flu, as a place to recuperate. A civil engineer, Uncle Walter was serving as a second lieutenant doing construction for the Air Service. He went to become public works commissioner for Manhattan and supervised construction of the East River Drive, among many other projects.

The spidery webs of wards and outbuildings on the hand drawn map of Base Hospital No. 6 have all since been replaced by modern neighborhoods, multi-story housing estates – including one called “Residence Crespy” probably after the chateau grounds on which it was built – and a Casino Supermarché. A large oval sports field behind the Lycée occupies the area where many of the wards and grand trees once sprawled. Surprisingly, the history of the Lycée on its website makes no mention of the hospital having been there, but wartime photographs match perfectly with the present-day view of the Lycée, as do photos of the nearby “Chateau du Breuil” which served as the nurses quarters. This now unnamed mansion is now nestled in a residential neighborhood, on Avenue du Chateau, near the corner of Avenue du Breuil.

During the hospital’s expansion in 1917-18, a fully equipped laboratory was established, where my grandfather was based with the other epidemiologists and technicians to identify and study pathologies. By June of 1918, “The laboratory rapidly expanded from a single room with two medical officers and two enlisted men to a fully equipped plant, consisting of a storeroom, office, clinical laboratory, bacteriological laboratory, clinical laboratory, water laboratory, autopsy room and morgue, and an animal house large enough to provide space for more than a thousand laboratory animals. … this elaborate plant was kept busy from morning until night, day in and day out, and fully justified its existence…” (William L. Moss, “Epidemiological Activities…” p. 98-99 in the 1924 account). A wartime photo shows three men posing at their benches, warmed by a wood-burning stove. Upon close inspection by my mother with a magnifying glass, and comparing with the ~1923 portrait above, the man second from the right is almost certainly Carl Binger.

The Influenza Pandemic of 1918

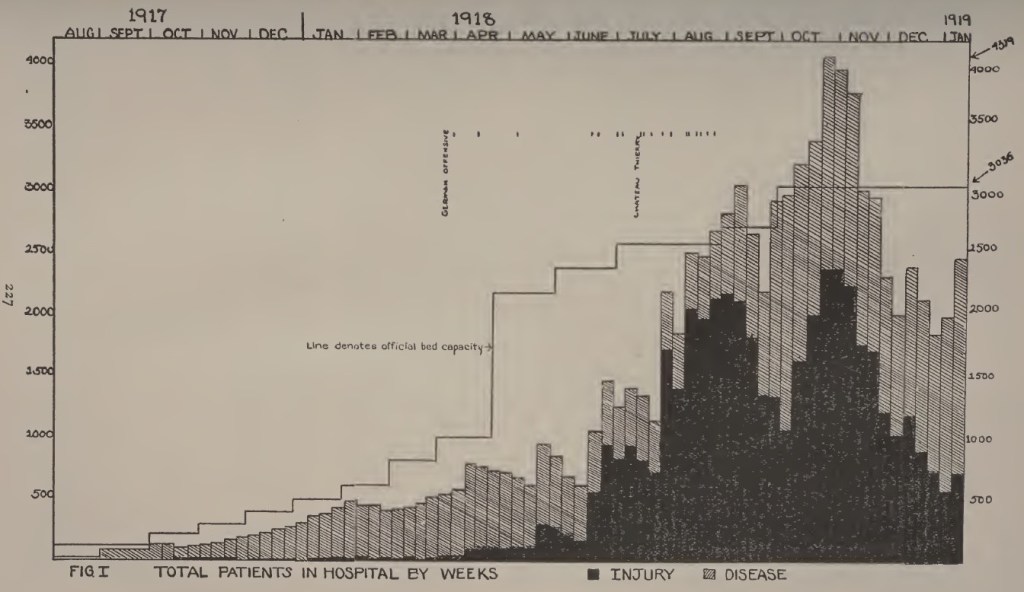

The hospital began receiving trainloads of sick and injured soldiers from the front in August 1917, but it seems that during the first 9 months or so things were fairly quiet and manageable. By June 2018 its capacity had been expanded to 3,000 beds, just in time for the influenza pandemic in addition to rising numbers of injuries. At the peak of the pandemic in the autumn of 2018 there were close to 4,500 patients. A hand-drawn chart shows the race to keep bed capacity ahead of patient numbers, and the peak of the curve bursting beyond the number of beds available. More than half were flu patients, and these constituted the majority of fatalities. However, influenza was not “reportable” as an illness until well into the pandemic, so cases were reported as “pneumonia”. Other diseases also wreaked havoc: meningitis, typhoid, typhus, cholera, measles, mumps and diphtheria, among others. There is a long history of armies becoming vectors of epidemics, and of disease killing more than combat, and WWI was no exception. Yet surprisingly epidemiology was not then a recognized division in the army’s medical organization.

The laboratory at Base Hospital No 6 was so well equipped and staffed that it was soon given responsibility for all of U.S. Base Section No. 2, which comprised about a sixth of France and 200,000 American soldiers in widely dispersed camps. Yet this turned out to be impractical due to the long distances and poor transportation, so smaller laboratories were set up at camp hospitals. Lieutenant Binger and his colleagues visited and supported these camps in a specially equipped laboratory bus. One of their first noted accomplishments came early in 1918, when a meningitis outbreak proved difficult to control. Binger was praised for discovering that the anti-meningitis serum being used had no potency, and with supervising its replacement with a stronger serum – a study then published in a medical journal in 1919. In the summer of 2018, my grandfather helped run MGH’s medical school at the hospital, training junior doctors, and he can be found on the timetable taking cohorts on rounds of the wards.

It was during the influenza contagion in the second half of 2018 that Lieutenant Binger really went to work as a field epidemiologist, going to army camps to deal with the worst outbreaks, putting in place isolation and quarantine measures, screening and separating sick soldiers, and helping to draft proposals to the military command for checking the pandemic – both as troops were mobilized and during the demobilization after armistice. He and his colleagues were notably disappointed that they were not able to discover anything new in their research on the pathogen, but they learned more about the kinds of bacteria in secondary pneumonia, and about effective measures for prevention and treatment. The following is a direct account from the 1924 history of Base Hospital No. 6 of Lieutenant Binger’s work on quarantine and recovery:

“The first outbreak of influenza which was attended with any mortality in Base Section No. 2, occurred during July, 1918 in the Mimizan District [on the coast south of Bordeaux], comprising five camps of Forestry Troops. Lieutenant Binger investigated this outbreak, and within twenty-four hours made a report covering the salient features of the situation. He was immediately put in charge, and within another twenty-four hours he had established a temporary camp hospital of a hundred beds, instituted adequate quarantine measures, and succeeded in keeping the disease out of the two camps which had not already become infected. He later established a convalescent camp of approximately one hundred beds, and remained in charge until the situation was well in hand.

“During the month of August, 1918, there was a serious outbreak of influenza in Camp Hunt at Le Courneau [an artillery training camp southeast of Bordeaux], where approximately 20,000 men were concentrated. Major Kinnicutt and Lieutenant Binger proceeded to Camp Hunt with the necessary laboratory equipment, and made valuable bacteriological studies of this outbreak. The disease was already too wide spread to speak with accuracy of its control, and it is doubtful if it would have been possible to control it, but they gave valuable aid in organizing and directing the care of the 1,000 bed camp hospital which was located at Le Courneau” (Moss, “Epidemiological Activities…” 1924, p 106)

Lieutenant Binger and his colleagues were not content to mitigate the outbreaks, and turned much of their attention to prevention. Soldiers with influenza were infecting one another in transit, in their camps, and on the front line, and the disease was taking thousands of soldiers out of duty, let alone taking their lives. The epidemiologists realized that the biggest risk of contagion came from the close proximity of sleeping quarters, and were critical of the dense placement of “quad bunks” (four attached bunks on two levels) in the widely used “Adrian Barrack”, a prefab structure 20 feet wide and 100 feet long. By regulation, there was meant to be 20 square feet per soldier, but this was not enforced. The epidemiologists of Base Section No 2 pushed hard for a new regulation of 40 square feet per soldier, and this was eventually approved but to their dismay was “emasculated by the words ‘where possible’” (p102). So they set about measuring billets in all the camps to identify violations of the 20 square foot rule, and convinced the Base Section commander to install partitions in quad beds. They also designed an open-air sleeping shed with partitions separating men into four groups of four, but by the time the pilot units were ready the war was over.

Perhaps the most impressive preventive measures taken by the epidemiologists in Base Hospital No 6 was the creation of a real-time data base of infections on index cards, updated daily with telegraphed or telephoned reports from all bases and camps in the section. “If all reports were not in by noon of the day following the twenty-four hour period covered by the report, the delinquent officers were called by long distance telephone and asked for their reports” (p103). Every single infection of every soldier, as detected, was entered on the cards, and reports were sent back to commanders in order to help them decide on troop movements without further spreading disease. While the medics were reluctant to appear to be advising on troop movements, “The value of this information [to commanders] was so apparent that in a short time it became an established practice to get the O.K. of the Base Surgeon’s office on all troop movement orders” (p104).

The data they collected also allowed real-time interventions to isolate infected soldiers and prevent further contagion. Lieutenant Binger and a colleague screened soldiers being transported urgently as replacements to the Western Front at the peak of the German offensive moving toward Paris. Many American troops were coming off their ships already infected. As my grandfather’s colleague William Moss writes, “Lieutenant Binger was sent to the 84th, and the writer to the 86th Division. In three days these two divisions had been combed through, the requisite number of replacements selected, and put on troop trains headed for the front. We were afterward told there was no outbreak of influenza among these troops, and a congratulatory telegram was received… on the way in which the matter was handled” (p108).

Quarantine was a sensitive issue, however, as it took men out of duty. So to convince commanders to cooperate, three levels of quarantine were established, and those with mild symptoms could still work outdoors. More importantly, the Base Section 2 epidemiologists challenged the convention of confining sick men to “Quarters” as this would risk spreading the illness to their “bunkies” (p105). At the peak of the influenza epidemic it became impractical to test everyone with influenza symptoms, so quarantine measures were simply based on observation of new symptomatic cases and efforts were taken to “draw a circle around it”.

One of the most interesting stories about my grandfather concerns his role in ending an epidemic affecting army horses at Camp de Souge, east of Bordeaux, which the army’s veterinary officers had been unable to contain. There were 7,000 – 8,000 horses at the camp, a third of them sick, and about 25 were dying each day. According to Moss, in the 1924 report:

“A plan of campaign was made which consisted in holding all horses coming to the camp in quarantine for a period of ten days, and admitting only those which were free from infection, segregating all the sick animals in the camp from those which were uninfected, thoroughly cleaning and disinfecting all the stables, corrals, watering troughs, harnesses, wagon poles, etc., white-washing all stables and corrals, and immediate condemnation and disposal of all hopelessly ill animals. Over a thousand of the infected animals were transferred to the veterinary hospital at Carbon Blanc. New corrals were built to accommodate another thousand animals within the camp, the hopelessly ill horses were shot and removed from the camp, and so well was the clean-up program carried out that within three weeks the epidemic was controlled, and Lieutenant Binger, who was placed in charge of this work, received a citation from GHQ in recognition.” (p107)

My efforts to find these various camps on Google Maps have been largely futile. The place names survive but any sign or mention of the camps have vanished. I imagine that if the French had to label every single site from the two world wars, there would be no room on the map for anything else. However, Camp de Souge is still very much there, just east of Bordeaux airport, and appears to be a military base. Streetview takes you along a barbed wire fence up to a barrier gate with guards, but not beyond, and satellite views reveal a sprawling complex with army trucks here and there, but no sign of any horses, stables or corrals. Signs of a ruined and overgrown complex at the far eastern edge of the base peaks my curiosity – could it be the remains of first World War stables?

Reflections on a pandemic

I imagine you have been struck, as I have been, by the many parallels between my grandfather’s experience of the 1918 influenza pandemic and our coronavirus pandemic, 102 years later. The limited scientific understanding of the pathogen. The intuitive and common-sense approach to isolation and quarantine. The detailed attention to measurements of distances and spaces to be maintained, and the difficulty of implementing this. The collection of real-time data, the plotting of graphs, the climb and flattening of curves. The failed race to keep bed capacity ahead of exponential numbers of patients. The pandemic’s peak at Base Hospital No. 6, a month before armistice, is reminiscent of today’s accounts of overwhelmed city hospitals in Wuhan, Milan, New York or London. As recalled in the 1924 account by my grandfather’s MGH colleague Richard D Cabot,

“When our hospital capacity amounted to 3,000, and finally to more than 4,000 patients, the quality of our work necessarily fell off. We were too much rushed and our personnel had suffered too much, – both in quality and relatively in numbers – to make it possible for us to maintain the high standard of the previous months. I do not know of any serious mistakes or disasters during that period, but I was in constant fear that such would occur, and in the days leading up to the armistice, it seemed as if the breaking point of fatigue and overwork was almost reached. Among the special features of our medical work to which I look back with satisfaction were the care of the cases of meningitis, given by Lieutenant Binger…” [and he goes on to commend other medical officers for their specific accomplishments] (p65)

I am also struck by the tension between medical priorities to save lives, and military priorities to mobilize troops to the front, where men were being killed and injured at staggering rates. The commanders demands for replacements, and the appeals of the medics for screening, isolation and safer sleeping quarters, remind me of today’s tug of war between advocates of social distancing and calls to re-open “the economy” even at the cost of lives. The medics had to find sympathetic allies in the command, and convince them that monitoring health data and mobilizing only healthy troops was better than spreading contagion through entire divisions. The need for consistent, system-wide data and coordination in addition to innovative, local level containment. The military approach to “fighting” an epidemic that has given us our language of “war against an invisible enemy”.

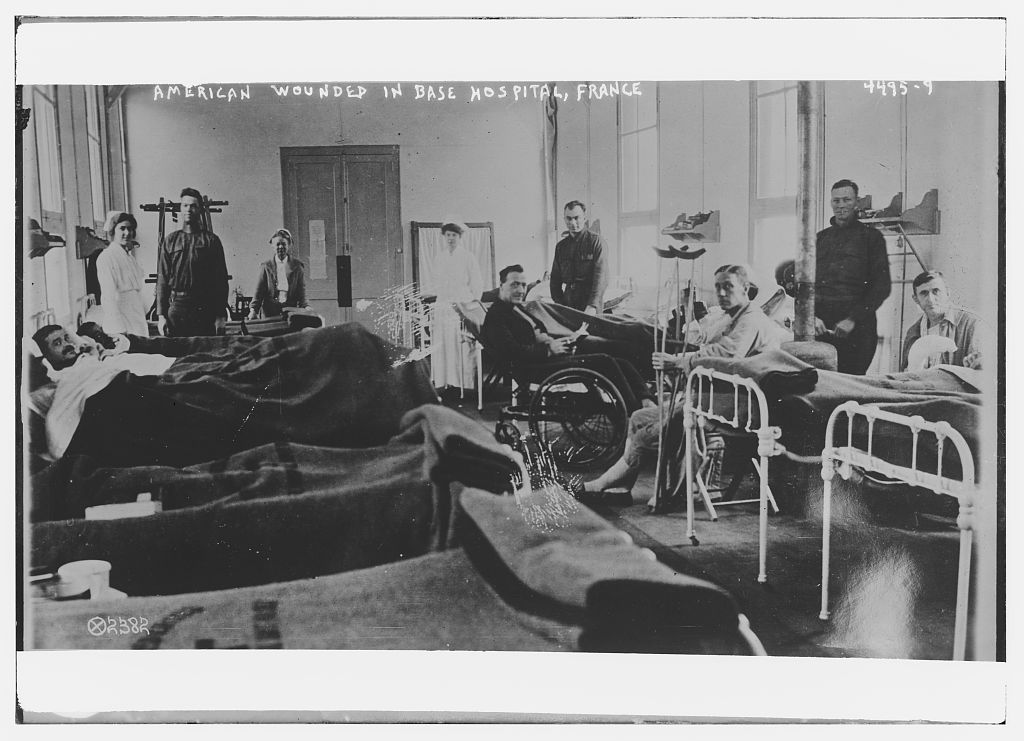

Another striking observation is the difference between the medical officers’ accounts and those of the nurses at Base Hospital No 6, who became known as the “Bordeaux Belles”. There is a website devoted to their stories, and a chapter in the 1924 history by head nurse Sara Parsons, which are more human and empathetic, and less formal and logistical than the male officers’ stories. The nurses made a tremendous effort not only to attend to the physical ailments of the sick and wounded, but to keep up their spirits and morale – organizing entertainment, decorating wards for holidays, baking cakes and making ice cream with money from their own pockets. The nurses were also mobilized to the front and were in the trenches for weeks at a time, cold and wet, without changing their clothes, to treat and evacuate the wounded. Their harrowing stories and the risks they took are also reminiscent of today’s frontline Covid-19 health workers.

Carl Binger after the war

After the armistice in November 1918, Base Hospital No 6 ceased to operate, as American soldiers were demobilized and as the sick and wounded had to get well enough to travel home. The medical staff were also tasked with screening out and isolating infected soldiers before embarkation, so as not to infect their shipmates, but this was a daunting task and relied only on a temperature check and a one-minute check-up. My mother has a letter from Carl Binger to his mother in 1918 in which he expressed his concern that infected soldiers were boarding ships, and warning that there would be a further epidemic in the US. Inevitably, many soldiers arrived in America with the flu, and it continued to spread into the civilian population, contributing to the famous second wave in 1919, which killed more than during 1918. By then I suppose Army censors had stopped minimizing the impact of the pandemic, or his letter snuck by them.

World War I and the susceptibility and movement of troops is widely credited with the exacerbating flu pandemic. According to Wikipedia, “The close quarters and massive troop movements… hastened the pandemic, and probably both increased transmission and augmented mutation. The war may also have increased the lethality of the virus. Some speculate the soldiers’ immune systems were weakened by malnourishment, as well as the stresses of combat and chemical attacks, increasing their susceptibility.” The first outbreak detected in the US was actually in January 1918 among soldiers being trained in Kansas, who then may have taken it to Europe – and there are theories that the disease originated in Kansas rather than in Spain. The second wave began in August and peaked in October 1918, testing the limits of Base Hospital No. 6 and infecting soldiers as they were demobilized. A third wave occurred in 1919. Unlike coronavirus, the pandemic mainly killed young adults; in the US 99% of deaths in the first were under 65.

American Base Hospital No 6 was closed in January 1919 and folded into the command of another Base Section 2 hospital. However, many of the MGH doctors stayed in Europe and were deployed on various humanitarian missions with the American Red Cross. My grandfather and five of his MGH colleagues were sent to Macedonia to help contain a typhus epidemic spreading with the arrival of war refugees, for which they were awarded medals. That is another story for another day, as is Carl Binger’s post war research on pulmonary medicine and oxygen therapies, and his venture into psychosomatic medicine.

However, another of Bici’s memories is worth mentioning here. She has a photograph of her father with his MGH colleague Paul Dudley White in the Peruvian Andes, with sleeping rolls on their shoulders, on an expedition to study the lung capacity of indigenous people in high altitudes. She remembers her father saying that they were suffering serious altitude sickness when the photo was taken. Paul Dudley White’s tenure at American Base Hospital No 6 is well documented, where he devised ground-breaking experiments to study the recovering lungs of gas attack victims. And as noted above, Carl Binger’s work on developing the iron lung and the portable oxygen tent eventually took him into the “psycho-biology” of breathing (with asthma patients, as my mother recalls), and an eventual career change into psychosomatic medicine.

My grandfather was married in 1926 to Clarinda Kirkham Garrison, granddaughter of the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and daughter of Wendell Philips Garrison, founding editor of The Nation. Carl and “Chloe” lived in New York City, on the upper east side of Manhattan, and had three children – David, Beatrice (my mother) and Katherine. In 1953 they moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts when Carl Binger was appointed psychiatrist at Harvard Health Services. My aunt Kilty (Katherine), who still lives on the upper east side, remembers the sad day the moving van came to take their belongings to Boston. One of the movers, she remembers, was “a powerful black man with one arm” and my grandfather, ever the curious doctor, asked him how he had lost his arm. Upon learning that it had been amputated in the war, and that he had been cared for at American Base Hospital No 6 in Bordeaux, “the two men embraced each other and wept”.

Sources

Center for the History of Medicine, Countway Library, Harvard University (online image archives)

Janice Brown, “The Nurses of Base Hospital No. 6, aka ‘Bordeaux Belles’”, website, http://www.cowhampshireblog.com/2017/04/18/new-hampshire-wwi-military-the-nurses-of-base-hospital-no-6-aka-the-bordeaux-belles/

Massachusetts General Hospital, 1924, The History of U.S. Army Base Hospital No. 6: And Its Part in the American Expeditionary Forces, 1917-1918, with particular reference to the chapters by Richard D Cabot and William L Moss. All page numbers refer to this document.

Interviews and emails with Katherine Binger Gilmour and Beatrice Binger Pettit-Barron, April 2020

Wikipedia, “The 1918 Flu Pandemic”, accessed April 2020

Photographs from various online archives, sources available. Portraits courtesy of Katherine and Beatrice.

An amazing account Jethro. I really enjoyed reading it so much. Gail Bach ( Dr. Bach’s wife)

LikeLike

Wow! I’ve heard some of this from your mom, Jethro, but what a fine ancestral history you’ve researched here! Thank you!

LikeLike

Jethro-What a powerful piece of work about an extraordinary man. A lovely birthday gift for Bici,too. At this time two friends and I , with a cast of 8 readers, are rehearsing a piece we have called “The Half-Life of War”. The basic idea behind it is that all wars leave traces down generations; the injuries are certainly not all physical. We have selected parts of letters and journals from the Revolutionary War down through WWII. Tomorrow at 4:30 we will have a ZOOM rehearsal. With your permission we might try to include a portion of your account of your grandfather’s work in the 1918 flu pandemic.

We can’t have ‘real’ rehearsals but somewhere along the line, we may try to have it filmed and offer the film instead of a ‘real’ performance, since there will be no large gatherings here this summer.

Stay well and someday we will meet at that lovely place Bici described in detail and which we hope to visit some day. Nan Lee

LikeLike

Thanks Nan, I totally agree with your idea of the “half-life of war” as trauma is passed from one generation to the next, often begetting new wars. Sebastian Faulks explores this beautifully in his interconnected novels spanning wars in the 20th century. I look forward to your production!

LikeLike

This is an outstanding history. I read it when it was first posted exactly a year ago, and I’m back to pick it up for a friend who’s doing some research.

LikeLike

thanks Ethan!

LikeLike

Thanks for putting this wonderful piece together, Jethro. Your grandfather shared some wonderful characteristics with his brother Walter, my grandfather–his formality, his ability to apply logic to the circumstances in which he found himself, and his energy. Those Binger boys led fascinating lives.

LikeLike

Thank you Lucie! I would love to learn more about Uncle Walter and his life and work, particularly his public works planning in New York city. Has anyone written any stories about him? All best wishes!

LikeLike